Written by: Averroes

Natrah and her tale:

Nadra binte Maarof (Natrah) or her Dutch name, Maria Huberdina Bertha Hertogh was a girl adopted by a Malay family, under Che Aminah. Maria's mother, Mrs. Adeline Hertogh had to give care of her to Che Aminah.

She was born in Tjimahi, Hava Island on 24th March 1937. She was Roman Catholic and baptised accordingly.

Che Aminah, in her fourties is a close friend of Adeline's mother, which resulted in the adoption and close ties. Moreover, the adoption was supposed to be temporary until the Japanese occupation was over.

She was struggling with her life, since her husband Mr. Adrianus Petus Hertogh (serving in the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army) became a Japanese prisoner in the Dutch East Indies on 8th March 1942.

When her father was captured, she was only 5 years old when the Japanese captured Singapore on 15th February 1942. She was the youngest of her five siblings.

As she was adopted by Che Aminah who lived in Bandung, Maria converted to Islam and was brought to Kemaman, Terengganu, living with her there.

She practised the Malay culture and spoke the language only. After the war, her biological parents went to look for her.

Scandalously, Natrah was dubbed as a 'Jungle Girl' by Western media because of her connections to Malaya. This prejudicial and insulting description of her imputes that Malaya was only infested with rabid animals and wild jungles.

She was also sensationalized in the Straits Tines of her struggle as to boost the Dutch and English morale after World War 2. It was because, if the British did not intervene in Natrah's case, the Dutch-English relations may sour.

When Mansoor Adabi, married Natrah on the 1st August 1950, it caught public attention. Since they got married three days, after Che Aminah won a legal case with the Dutch Consul in Singapore for the custody of Natrah.

However, the marriage was criticised because all legal remedies have not been exhausted and Natrah's status to remain in Malaya is technically still ongoing subject to appeals.

Legal Battle:

Natrah's case involved Family Law which came before the Singaporean courts. The issues revolved around the custody by the biological parents and the foster/adopted Malay family. The court applied the English, Dutch and Malay or Muslim customary law.

Should Natrah maintain her welfare and life in Malaya or start afresh in Holland. It was only in 1949, when an English District Officer, Arthur Locke arrived in Terengganu and saw Natrah studying among the Malay community. He discovered that it was the White girl who was being searched for and informed the Dutch Consulate in Singapore.

Che Aminah was told that she could have proper adoption of Natrah through legal documents and travel to Holland to meet her parents for such purpose. When Che Aminah arrived in Singapore, she was tricked and she was given $500 to return Natrah to her biological family. She rejected it.

The Dutch Consul (Jacob van der Gaag) obtained a High Court order on 22 April 1950 through ex parte application under the Guardianship of Infants Ordinance that her custody was given to the Social Welfare Department, pending further order. Che Aminah had to surrender Natrah to them.

Che Aminah applied to be party to the proceedings and order was granted on 28th April 1950.

The Chief Justice of the Court of Appeal dated 19th May 1950, held that Natrah should be under the care and custody of the Dutch Consul, to restore her to her biological parents.

Che Aminah appealed the decision by the Justice of the Court of Appeal, and it was held that the action of the Dutch Consul amounted to an abuse of process and had no locus standi, as he was not acting as the agent of the father, but as consul only. It was abuse of court process to retain Natrah in Singapore.

Moreover, the proceedings was null and void, as the Che Aminah and Natrah were not properly served copies of the orders as required by the Rules of the British Supreme Court.

Therefore, Natrah was released and returned back to Che Aminah.

The Final Outcome:

As mentioned before, after Natrah was released, she was married to Mansoor Adabi three days later, who was a young man from Kelantan. According to Malay-Muslim law, even if she was 13, below the standard of age of majority, she was considered mature and had the capacity to marry.

The Imam testified in court that he was competent to solemnise the marriage and be her wali. Later, the Dutch family finally arrived in Singapore and wanted to challenge the custody of Natrah, after the Dutch Consul failed.

The Dutch family was even sponsored $80,000 guilders raised within a span of a few weeks for legal representation which angered Muslims in Pakistan, Indonesia and even in Saudi Arabia.

They commenced action under the Guardianship of Infants Ordinance. It was through an Originating Summons in the High Court of Singapore.

The first issue is when was the adoption in 1942. The court refused to answer this issue, since both parties were asserting false testimonies. .

The second issue is whether the court has jurisdiction under the Guardianship of Infants Ordinance to declare Natrah's marriage valid or otherwise. As per Brown J, it was held that Natrah is to be returned to the custody of her biological parents in the Netherlands.

He elaborated that the marriage was void, as she was 13 and not bound by the local Malay marriage laws. She was still bound by the domicile law of her father, which was Dutch Law. Natrah did not have the capacity to marry as she was below 16 years old.

There was an exception to this law and that is, if she married her husband, she would follow the domicile law of her husband, which is Mansoor Adabi. Therefore, she would actually be bound by Malay-Islamic law.

Court found that Mansoor Adabi was not domiciled in Singapore and that even if she converted to Islam, a minor could not consent. The consent rests within the father as he had the power to control the religion, education and general upbringing of his child.

Though, court did state they will not grant custody, if the father was unfit to exercise or he himself was abrogated. To conclude, the court alluded on the issue of best interest or welfare of children from the father.

The child has the best interest when she is with her biological father and he has the right. Natrah would have a better life in the Netherlands.

Che Aminah made a final appeal but was dismissed. Soon on 12th December 1950, she was flown back to Holland. Even an application of stay by Che Aminah on 11th December 1950 was rejected.

The Ramifications:

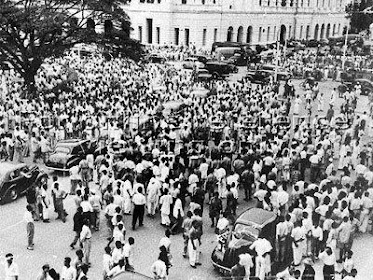

As a result of the court decision, the whole world as well as Malaya, particularly in Singapore rioted to protest the court's decision, which incited racial and religious sensitivities and dissatisfaction. Until today in Malaysia, race and religion is a polemic topic.

They believed that Natrah was coerced to convert to Christianity and thousands of Muslims from the Malay and Indian community gathered which lasted for 4 days between 11-14th December 1950 to riot.

It initiated when a Eurasian Volunteer Police Officer wounded two Malays, which escalated into sporadic attacks, arsons, robbery, murder and other forms of violence. Malay police officers also refused to participate in the crackdown and was slow to react to the riots.

The riots took place in Kampong Glam, North Bridge Road, Tanjong Katong and Geylang Road.

This riot sent a signal that the defences in Malaya were so weak, the communists could take over and it became a hot topic in the UK Parliament.

There was an image on the Straits Times which depicted Natrah crying inside a church while she was being consoled by a nun. However, the title of the news article was contradictory, as it said that she was crying from joy, but actually crying from missing Malaya and her adopted family there.

Hence, the separation of Natrah and her adopted family resulted in a psychological impact toward her. Moreover, in Malaya and under Malay customs and Islam, Natrah was fit for marriage as she had reached puberty or maturity at the age of 14, rather than reaching the age of majority.

Therefore, she is able to decide for herself and is now subjected to Islamic law, rather than Christian or Dutch law. No coercion was involved. The court did not consider the interest of Natrah herself and gave her the ability to choose which family she preferred.

Moreover, she married to an educated man at the age of 22 who was a probationary teacher and not some random bloke from the streets. He was able to sustain and support her life until death do they part. Che Aminah herself was a rich businesswoman and denies that she was a nurse or a maid to the Hertogh's in Indonesia.

She has since lived for a very long time with Che Aminah and had been taken care of by her adopted mother. If her biological mother cared for her, why would she let go of Natrah to someone else?

Natrah clearly unhappy with her biological mother

The issue of underage marriage sparked greater with the British planning to introduce the Laycock Marriage Bill (marriages under 16 years old are void), prompting mixed reactions among the Malayan locals. The Bill excluded Muslims eventually.

Maria ended up homesick of Malaya, she had a bitter relationship with her mother and told the press that she never wanted to go back to Holland. She lacked attention from her mother since there were 5 other siblings.

She eventually married a Dutch soldier, but had a rocky marriage which ended in divorce from an irretrievable breakdown. She plotted to kill him in 1976. She was charged in court, but was acquitted due to her dismal past.

References;

Syed Muhd Khairudin Aljunied. (2008) The Aftermath of The Maria Hertogh Riots in Colonial Singapore (1950-1953) Department of History. School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). Unviersoty of London. A Thesis Submitted for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PHD).

Keong, C. (2012) Multculturalism in Singapore - The Way to a Harmonious Society. The International Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers (IAML) Audrey Ducroux Memorial Lecture.

Mohd Firdaus Abdullah, Arba'iyah Mohd Noor, Mohd Shahrul Azha Mohd Sharif, Norasmahani Hussain & Norazilawati Abd Wahab. (2021) Di Sebalik Isu Natrah, 1950: Reaksi Pembaca The Straits Times terhadap Tragedi Natrah. Journal of Al-Tamaddun. 16(1), Pp 47-64. Retrieved from, https://doi.org/10.22452/JAT.vol16no1.4

Comments

Post a Comment